A Painter’s Retreat: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George

Glen Falls, NY — An ambitious exhibition on view this summer at the Hyde Collection is the first of its kind to explore the formative influence of Lake George on the art and life of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986). O’Keeffe, the great Maiden of American Modernism, is celebrated most for the existential

Glen Falls, NY — An ambitious exhibition on view this summer at the Hyde Collection is the first of its kind to explore the formative influence of Lake George on the art and life of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986). O’Keeffe, the great Maiden of American Modernism, is celebrated most for the existential paintings she created out in the dry air of New Mexico, but as this exhibition attests, the works painted on the shore and in the hills around New York’s Lake George are among the most prolific and transformative of her seven-decade career.

The Hyde Collection is an extraordinary place, one of the few of its kind in upstate New York. A product of the golden age of the private art collector, it’s a prime example of the rare genre of museums created during the American Renaissance. Turned into a public museum by Charlotte Pruyn Hyde in 1952, she dedicated her estate and art collection to the community. Her two story house — the Hyde House — was constructed between 1910 and 1912 in the style of an Italian Renaissance palazzo and architecturally inspired by the Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Fenway Court in Boston.

The collection within consists of over 3,330 objects that span the history of Western art from Old Masters such as Sandro Botticelli, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, and El Greco’s “Portrait of St. James the Less” to modern masters such as Matisse and blue period Picasso in Mrs. Hyde’s Bedroom. The Hyde also contains a fine assortment of American art, with works by George Bellows, Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer and — my favorite discovery — an Arthur B. Davies painting of Salt Lake, Utah, hanging in the Down Guest Bedroom. The O’Keeffe exhibition is located in the Woodward Gallery a modern building located adjacent to the Hyde House. It’s a fitting venue for an intimate look at O’Keeffe.

Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George offers sixty paintings dating from 1918-1934. Curated by Erin B. Coe (Chief Curator at the Hyde), and Barbara Buhler Lynes (former curator of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum), the exhibit is divided into six themes: Landscapes, Barns and Buildings, Abstractions, Tree Portraits, From the Garden, and Lake George Souvenirs. The exhibition also includes significant loans from dozens of major collecting institutions from across the United States and is quite a coup for the Hyde.

O’Keeffe’s relationship with Lake George dates back to the time surrounding when she declared her interest in becoming a painter. As a young student in 1908 she won the William Merritt Chase Still Life Prize from the Art Students League, New York. The award offered her a place in the League’s outdoor summer school at Amitola on Lake George. The summer would have a lasting impression, as it would mark the first time O’Keeffe painted outdoors. The experiences that summer would lead quite possibly, as Hunter Drohojowska-Phillips suggested in his book Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O’Keeffe, “to her realization that the landscape could act as metaphor for the tumult of emotion.”

Ten years later, in June 1918, having exhibited with Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 the year prior, O’Keeffe accepted Stieglitz’s invitation to move to New York permanently and devote herself entirely to her art. Later that year, O’Keeffe made her first sojourn to the Stieglitz’s family estate situated just north of Lake George Village along the western shoreline of Lake George in New York’s Adirondack Park. The estate would serve as a rural retreat for O’Keeffe from 1918 to 1934 and the artist’s most productive period of her career creating more than 200 paintings on canvas and paper in addition to sketches and pastels.

O’Keeffe sought to transcribe ineffable thoughts and emotions through many of her early abstractions. Very often the composition evoked the spirit of place, which became essential to her modern approach to the natural world. In 1918, O’Keeffe began a series of abstract paintings titled simply Series I. This series was the subject of an important study of O’Keeffe’s largely unexplored oeuvre organized by the Whitney Museum five years ago. The Whitney exhibition was celebrated as an overdue acknowledgment of her place as one of America’s first abstract artists. Two examples from this series, both painted at Lake George in 1919, Series I-No. 10A and Series I, No. 10 are on view at the Hyde.

Lake George, Coat and Red (1919) is a strong little painting on loan from the Museum of Modern Art. Vibrant in color with high chromes of red and blue, the work brings to mind the era of early American Modernism, recalling the works of Stanton MacDonald-Wright (whom Stieglitz also actively supported). Yet O’Keeffe’s work is much more assertive in its composition and deliberate in its brushwork. It’s suggested that the large swelling form is an evocation of Stieglitz himself, who often wore a dark cape lined in red.

O’Keeffe liked to paint what she saw and at Lake George she learned to paint on the spot. “Lake George with Crows” (1921) captures O’Keeffe’s blunt spontaneity. Three crows circle the center of the dark blue lake. Deep autumnal mountains cut the composition from upper left to lower right exposing slightly a cloud-covered moon sitting high in a silvery sky. It is O’Keeffe at her greatest, where she deliberately defines space then allows the paint to organically express her vision. “Lake George with Crows” is one of the rare times O’Keeffe ever painted birds.

“I wish you could see the place here,” O’Keeffe wrote to the writer Sherwood Anderson from Lake George, “there is something so perfect about the mountains and the lake and the trees-Sometimes I want to tear it all to pieces—it seems so perfect-but it is really lovely […]”

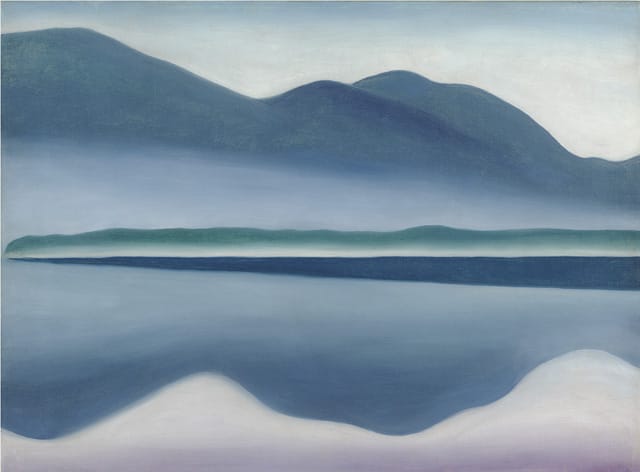

O’Keeffe completed twenty landscapes while at Lake George. Many following similar, yet essential, composition elements as seen in “Lake George” (formerly “Reflection Seascape”) (1922) with its long band of lake as horizon and a distinctive mountain range as seen from the Stieglitz’s Estate. With its subtle greens and smoky grays the painting captures a slow and sublime pace of her summer retreat.

O’Keeffe often spoke about painting “like the men do.” It’s hard not to see a little Van Gogh in O’Keeffe’s “Starlight Night, Lake George” (1922). Painted in the fall of 1922, the stars hover in orbits in a deep blue night’s sky while two lights glimmer, reflect in the lake. The organic undulation of the water is O’Keeffe at her best as we all but feel the cool breeze rippling off the dark lake. The work is a mature incarnation of an earlier work, the watercolor, “Starlight Night” (1917), which so pleased her that she later had it reproduced as her Christmas card.

O’Keeffe’s fascination with trees overtook her interest in the lake. In all, she painted twenty-nine arboreal portraits of which many are on view at the Hyde. Three in particular, “Tree with Cut Limb” (1920), “The Chestnut Grey” (1924), and “The Old Maple, Lake George” (1926) where among my favorite as O’Keeffe imbues each with a distinct emotion. In “Tree with Cut Limb” we sympathize with the pain of a severed branch. In “The Chestnut Grey,” we partake of the wisdom whispered through the wind of the Chestnut’s aged and lumberous limbs. She painted the same tree twice, once at sunrise and this one at sunset. “If only people were trees…” O’Keeffe told an interviewer in 1927, “I might like them better.”

O’Keeffe closely crops the composition of “The Old Maple, Lake George” (1926) to bring us closer to the gnarled surface of the old tree which she paints like old bones. “The Old Maple” is a prelude of the O’Keeffe to come. Returning to Lake George from her first trip out west in 1929, O’Keeffe brought back “a barrel of bones.” As she describes in the 1977 documentary of her work:

When it was time to go home, I felt as though I hadn’t even started on the country and I wondered what I could take home that I could continue what I felt about the country and I couldn’t think of anything to take home but a barrel of bones. So when I got home with my barrel of bones to Lake George, I stayed up there quite a while that fall and painted. That’s where I painted my first skulls, from this barrel of bones.

The resulting paintings would become two of her most celebrated compositions. First, “Horse’s Skull on Blue” (1930), and second “Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue” (1931).

While representational imagery dominated the Lake George years, pure abstraction remained at the heart of her work. I was thrilled to see three magnificent examples in the exhibition at the Hyde including “From the Lake, No. 3” (1924), “Pink Abstraction” (1929) and “Green Grey Abstraction” (1931). “Pink Abstraction” was painted during a spring visit to Lake George. “Green Grey Abstraction” was considered by O’Keeffe to be a portrait, a work like many “that have passed into abstraction while no one really knew what they were,” she said in 1976. “Green Grey” was a gift to Jane Weinberg in 1954 purchased from Downtown Gallery by her husband to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary. Ms. Weinberg tells a wonderful story of meeting O’Keeffe:

I asked her if she would tell me about [the painting]. [O’Keeffe] froze and said only, “It’s all there.”

[…] [O’Keeffe] asked if I had read the Art of Zen Archery. I had and had been interested and impressed by it. She said the painting was like that; it wasn’t part of any series; it had come out whole and she never had to change it or make another. Usually she knew ahead of time what she wanted to paint, but had to work on her paintings. This one was different. Had I noticed the star on the back of the painting? She only put stars on paintings she especially liked.

It is typical of O’Keeffe to suggest that the most abstract image might be most meaningful. As the exhibition at the Hyde suggests, it was at Lake George that she realized that she did not desire to capture the surface appearance of things. Instead, she labored to eliminate some things and emphasize others in order to, as she put it, “get at the real meaning of things.”

There are wonderful examples of paintings of apples and fallen leaves in the exhibition as well as red cannas and grey barns. And there is on view the only painting she made of apple blossoms.

A final series of paintings titled Jack-in-Pulpit (1930), in which No. II-VI are on exhibit, offers an analytical step-by-step progression of O’Keeffe’s move towards abstraction. The series begins with the striped hooded bloom rendered with her distinct botanist’s care, continues with successively more abstract and tightly focused depictions, and ends with the essence of the jack-in-the-pulpit, a haloed black pistil standing alone against a black, purple, and gray field. As if the flower was a problem she was trying to solve, O’Keeffe systematically eliminates, crops, and tucks, reducing the observable world into its most essential, meaningful form. O’Keeffe explains here:

I have a series of paintings of Jack-in-the Pulpits. At Lake George we had a good many Jack-in-the-Pulpits. My first one was almost photographic. It was about 10×12. And the next one got up to be 30×36. And the next one was 30×40. And in that one the jack got black. Well, then I made an abstract thing of all the different parts of the jack and then it got to be 48 inches high. And then I thought I ought to be able to simplify it more than that, and then I thought well the thing that makes you interested in that flower, and that you wouldn’t look at the flower without, is the jack in the middle of it. So I painted just the jack.

After her she discovered New Mexico, O’Keeffe would spend less and less time in Lake George. As she put it she had found “her country.” By the early 1930s she had established a routine of heading to Ghost Ranch for the summer, returning to Lake George in the late fall (her favorite season) and spending the winter in New York City where she still took responsibility for Stieglitz’s day to day needs.

“The Lake George years in my view are so vitally important,” Curator Erin B. Coe recently told North Country Public Radio, “because they coincide with [O’Keeffe’s] devolvement and evolution as an artist and really set the stage for her entire career.”

This exhibition does much to illustrate that her experiences on Lake George remained with her for rest of her brilliant career. To see so many works returned to their place of origin, is the greatest aspect of this show. I think even grumpy old O’Keeffe herself would find some cheer in that.

Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George is on view at The Hyde Collection (161 Warren Streeet, Glens Falls, New York) through September 15, 2013 after which it will tour to Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, NM, October 4, 2013-January 26, 2004 and Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, de Young Museum, February 8-May 11, 2014. A full illustrated catalogue with essays by Erin B. Coe, Bruce Robertson, and Gwendolyn Owens accompanies the exhibition.